ORFEO International – Reviews

Important Releases Briefly Introduced

March 2016

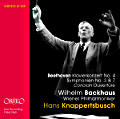

ORFEO 2 CD C 901 162 B

Knappertsbusch: Beethoven

The Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra enjoys a special position, not least because – besides its activities in the pit of the Vienna State Opera – it is constituted as an autonomous concert orchestra (something one easily forgets). This means that it is able to establish a very particular relationship with the guest conductors it chooses. In some cases, that relationship has been especially long-lasting and intense. Hans Knappertsbusch (born 1888 in Elberfeld) first encountered the orchestra in 1929 in Salzburg, but by the time of his death in 1964 they had together given no less than 210 concerts – not to mention innumerable performances at the Vienna State Opera.

This singular, unique man was physically imposing, and while he was demonstratively averse to courting publicity, he seemed at the same time not wholly unaware that he was also the object of immense admiration and love on the part of his audiences. He was notorious for almost daringly minimalistic rehearsals – and, up to a certain point, he was loved for it all the more by his orchestras. And not all his various comments on musicians (male and female), colleagues and (modern) composers are of a nature that may be quoted in print. He kept to a relatively small repertoire comprising the masterworks of which he was particularly fond, and in his interpretations of them he developed over the years a brilliantly intuitive, calm, deliberate mental disposition that was paired with a high degree of emotional spontaneity and intense, sometimes abrupt expression.

This characteristic mixture can understandably

C 901 162 Bbe experienced far better in his live concert recordings than in his studio recordings (which he did not particularly like making anyway). In this he was a typical representative of a generation for whom music-making could not be easily combined with the studio perfection that was later required (let alone the efforts – more or less unconscious – that other conductors made to adjust to this clinical perfection in advance of the studio). The “test run” of an act from the Walküre that Decca made with him and with the young Solti, with a view to a complete recording of the Ring, is legendary today – and we all know how that ended.

As with several of his later colleagues, Knappertsbuschs’s approach to Beethoven is a special case within the “special case” that was Knappertsbusch himself; he was above all known as a conductor of the “heavier” German late Romantics. In his finest moments, his high degree of unpredictability (something which marks him out as the complete opposite of his great colleague and competitor Karajan) affords his interpretations a sense of “recreating” the music in the truest sense of the word, making it sound as if it is being played “for the first-ever time”. And this is probably why the music in these moments sounds so powerful, refreshing and liberating, far removed from any kind of comfortable listening conventions. And today, in retrospect, it also sounds free of any new-fangled fashions or constraints. Expressive details are always granted the time they need, as is the overall context. We never come across a tempo that is too fast, however historically well-founded it might have been. But nor is there any sense of “titanic” expression (whatever that is supposed to be). And in the process, however different in character his various performances of a single work might be, the whole work always comes across as balanced and coherent in itself on a higher level. In short: the characteristics of Knappertsbusch’s art of music-making are particularly inspiring in the case of Beethoven – a composer whose music is both rational and constructive, and yet soars freely into new regions of the imagination.

On this new double CD we can hear both a complete concert given in the Musikverein in Vienna on 17 January 1954 – with the Coriolanus Overture, the Fourth Piano Concerto and the Seventh Symphony – and the Third Symphony from a concert at the same venue, given on 17 February 1962. In the unheroic G-major Piano Concerto, Knappertsbusch’s partner is his contemporary Backhaus, who was famous for his Beethoven, but who at the same time possessed an individual “objectivity” and a legendary virtuosity that doubly refutes the clichés about “typically German” musicians. In this context, the commentator Gottfried Kraus recalls visiting Backhaus’s apartment in Salzburg, where the pianist spoke of his lifelong struggle to play the problematic lyrical chords at the opening of this Concerto. In the third movement, we are also wrenched from our customary listening habits by an unknown cadenza – and then cast back, bewildered, onto the well-known, yet seemingly new paths of the Concerto once again. The best performers can play the great masterpieces in so many different ways because the works themselves are far greater than any individual interpretation.

top |