ORFEO International – Catalogue

CDs

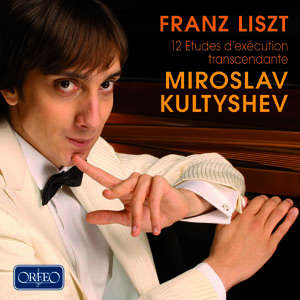

| Franz Liszt

Douze Etudes d'exécution transcendante Orfeo • 1 CD • 63min Order No.: C 759 081 A |

|

Composers/Works: |

F. Liszt: Douze Etudes d'exécution transcendante S 139

|

Artists: |

Miroslav Kultyshev (Klavier)

|

Miroslav Kultyshev

The Russian pianist Miroslav Kultyshev was still a child when he discovered his altogether exceptional gifts as a musician. Not yet in his mid-twenties, he is now a regular visitor to all the world’s major concert halls. The holder of scholarships from the Yuri Bashmet Foundation and the St Petersburg Philharmonic Society, among others, he has already appeared in the Großer Saal of the Vienna Musikverein, the Amsterdam Concertgebouw and New York’s Avery Fisher Hall. He has worked especially closely with the conductor Valery Gergiev, and the two have appeared together in numerous halls and at several festivals.

C 759 081 AFor Orfeo he has recorded Franz Liszt’s quintessentially Romantic Études d’exécution transcendante, a cycle of twelve piano pieces that is arguably the most technically difficult of all such cycles as well as being the most challenging from a purely musical point of view. The result is striking and instantly infectious: Kultyshev is one of those hand-picked pianists who are not only capable of unleashing the full force of Liszt’s ensorcellments without apparent difficulty but who are also able to fill the work to the very brim with passion and life. This is due in part to Kultyshev’s ability to phrase even the most demanding passages and climaxes organically, be they chordal or polyphonic, be they wide-ranging intervals or breakneck runs: not for a moment does he slow down randomly to compensate for technical deficiencies, but nor does he speed up in pursuit of empty effects. But it is also due to the fact that Kultyshev is already a past master at mixing Romantic tone colours, notably in the second study in A minor (“a capriccio”), with its radiant upper voice in the treble and accompanying chords far below it. In Mazeppa he is able to integrate the motif of the revolutionary song into the furious basic movement, giving it its proper weight and ultimately bringing to it a very real sense of triumph, whereas the major-key variant in the middle section is beautifully understated in its cantabilità. But however much artifice may lie behind these magisterial performances and however sensitive Kultyshev’s musicality may be, his interpretation surprises us and appeals to us with rare immediacy because he is so clearly in total command of his instrument and intellectually imbued with the whole cycle and, above all, because of his resultant emotional and, indeed, impassioned identification with all twelve of these pieces. There is something almost terrifying about this identification, and in so young an artist it is certainly astonishing. In general, Kultyshev seems altogether predestined to succeed most of all with the atmospherically dense impressions of nature that Liszt has included in these studies, from Feux follets, the iridescent chromaticisms of which are fully in keeping with the piece’s title, to the darkly sonorous glow of Harmonies du soir and, finally, to the evocative, wintry landscape of Chasseneige, which brings this set of twelve transcendental studies to its atmospheric conclusion.

|